|

|

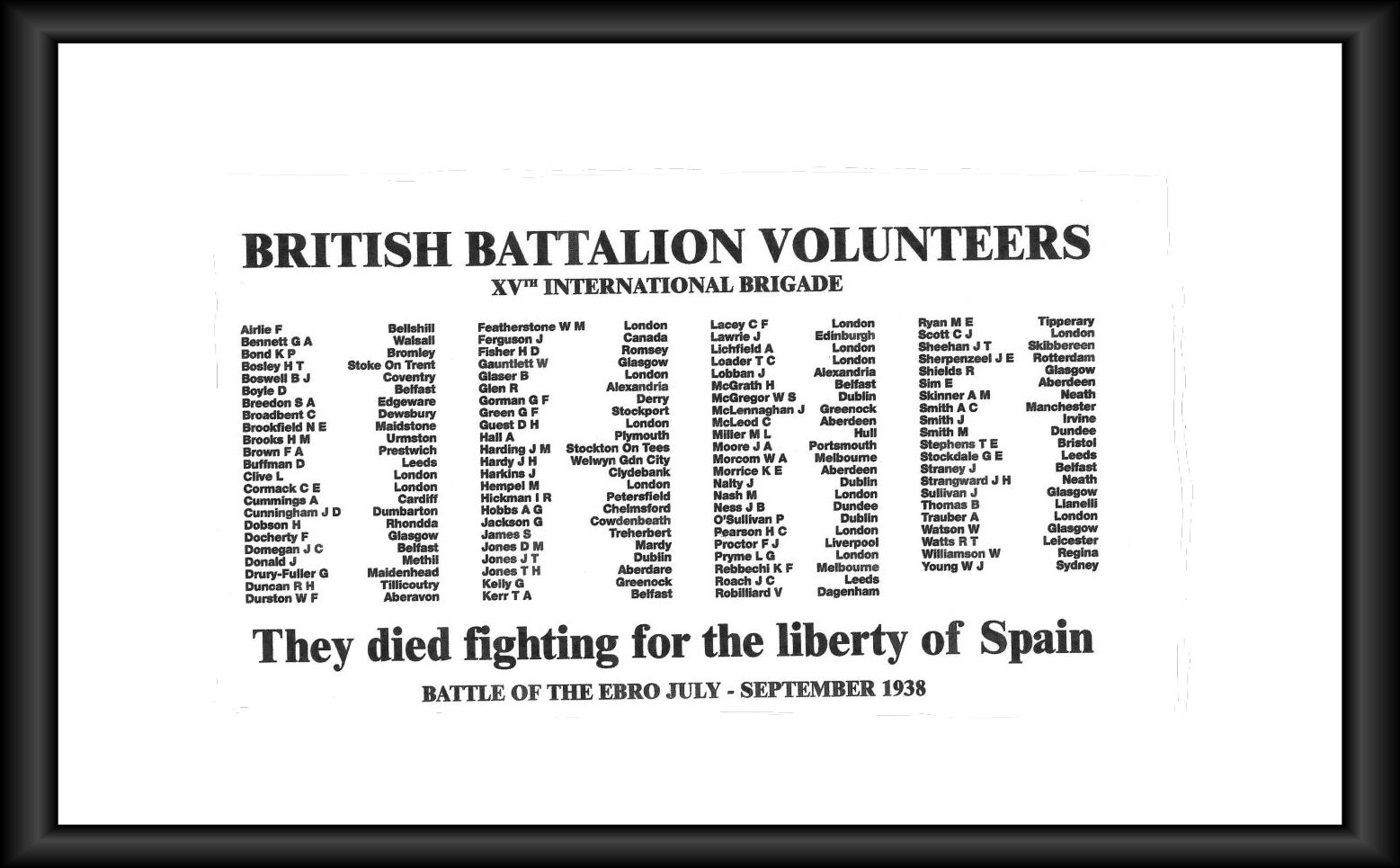

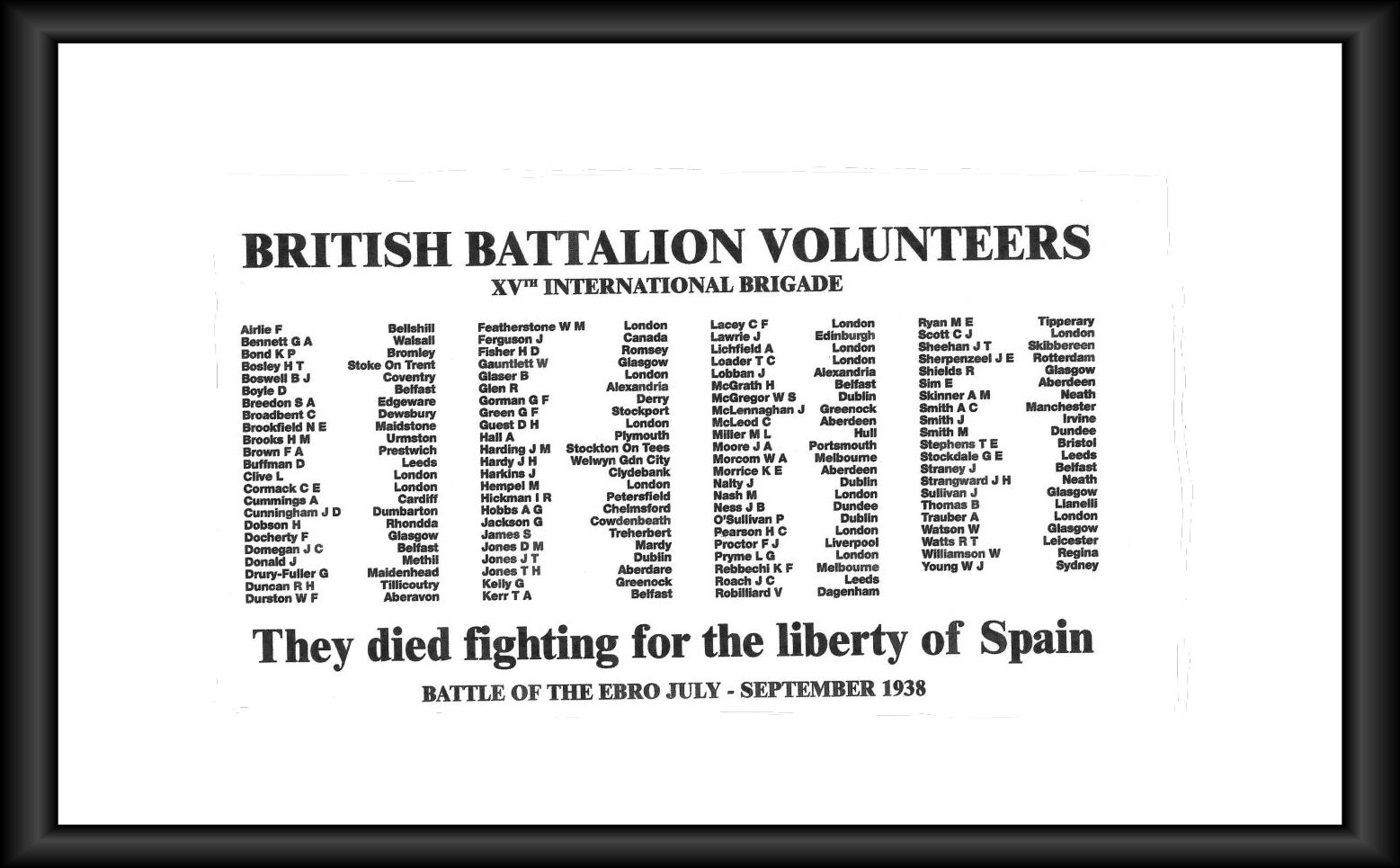

To those that are unaware of the subject, there is often a sense of shock or surprise, when they first learn of the historical links between Wales and Spain. Later, this often turns to admiration and respect when they hear that a large number of Welshmen volunteered to travel to Spain to fight fascism, as part of an International Brigade, during the Civil War that enveloped the country during the 1930s. These included men such as Jack Jones and Will Paynter, both of Tonypandy, Morien Morgan of Ynysybwl (Stradling, 2004: 184-5) and William Lloyd of Aberdare (Francis, 1984; 161). Some like Tom Howell Jones of Aberdare (BBC Documentary, 1979) and Ramon Rodriguez, one of three Welsh-Spaniards to volunteer, would pay the ultimate sacrifice in this valiant attempt to help others, never to return (Hopkins, 1998: 388). The actual number of Welsh volunteers is often disputed, mainly due to the fact that the men were just that, volunteers. Britain had adopted a Non-Intervention policy which forbade British people from participating in the armed struggle. Consequently, men would travel with the aim of avoiding detection. Figures vary from between 170 and 200 men (Cynon Valley Leader, 2007). For example, a total of 178 Welsh volunteers and thirty-three resultant fatalities are quoted in the BBC documentary, Colliers Crusade (1979), whilst a figure of 174 volunteers is stated by Evans (2000: 95). Of these, 122 were miners from the South Wales coalfield (Francis & Smith, 1998; 354) and over 72 per cent were Communist Party members with a quarter of all the volunteers being Trade Union members (Evans: 95). Some had also experienced victimisation for their union activities (Francis, 1970). Many of the men were also over thirty years of age, married and had suffered unemployment for long periods of time (Francis, 1970). No matter what the statistics though, many questions arise. What caused these men from a small country like Wales to leave their families and friends to volunteer and fight in a foreign conflict? A struggle that was regarded by many including volunteer, Tom Jones, as the actual start of the Second World War (BBC Documentary, 1979). Some of the volunteers like Lance Rogers, Harry Stratton and Tim Harrington did so without the knowledge of aforementioned family and friends (BBC 2 Wales, 2006: Francis, 1991) and all knew they were contravening British law by actively participating. It was inevitably an episode that was to have a profound effect on all of those who volunteered. It is possible that the majority, during some stage of their voluntary engagement, would have uttered the famous Republican cry, No Pasaran! They Shall Not Pass! (Cazarlo-Sanzech, 2005). However, as Lance Rogers commented in later life, ‘There is no glory in war. War is an emblem of hell and each and every soldier a hired assassin used to settle quarrels he never made’ (BBC2 Wales, 2006). In this study we shall examine the political and social reasons and the motivation that guided such men in making such a sacrifice. What was going on within interwar South Wales that could trigger such a reaction and indeed, can we actually draw a correlation between the two?

In attempting to address these questions, we need to examine what the underlying situation was like in both Spain and Wales during this period and gauge the connecting factors. What was this country like that so many men were volunteering to fight in? Well, Spain had essentially been a feudal country with a military dictatorship and the plight of the agricultural peasant in particular was grim. Levels of extreme poverty were high and the Roman Catholic Church held great power across the country. The newly elected government of 1931 had overseen the transition of Spain to a democratic Republic and there was a strong desire to bring the country into the modern era. However, support for the new government was deeply fragmented and disagreements soon arose (BBC Documentary, 1979). Alas, this alienated the powerful and traditional sectors of Spanish society, which culminated in periods of both right and left wing control. As the situation gradually deteriorated, military commander, General Francisco Franco proclaimed an alternative government. Matters soon spiraled out of control and civil war ensued in July 1936. Whilst Franco and the Nationalists, supported by Germany and Italy, perceived it as a fight against communism, the Republicans with support from Stalin viewed it as a struggle between democracy and fascism. (AGOR, 2008).

In relation to Wales, just two months before the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, the President of the South Wales Miners Federation, Arthur Horner, had issued the following statement to an anti-fascist rally in the Rhondda Valley:

The fight against fascism is the fight for trade unionism…one hundred per cent conscious militant trade unionism is the most important safeguard against fascism…Scab unionism is fascism in embryo.

(Cited in Francis, 1970)

The miners of South Wales strongly identified with the struggles of the Spanish people and couldcertainly empathise with the problem of poverty but as Francis (1984: 23) declares, the, ‘reaction was one of solidarity and admiration for the courage of the Spanish people rather than of distanced sympathy’. For men like Jack Roberts, an unemployed miner from Abertridwr near Caerphilly, otherwise known as Jack Russia, ‘…the clash in Spain was the logical extension of his political battles at home. The fight of the Spanish people for democratic freedom was the fight of workers everywhere’ (Felstead, 1981: 35).With the Russian Revolution still fresh in people’s minds, he believed that what was going on in Wales was part of an ongoing process that could eventually lead to worldwide revolution (BBC Documentary, 1979).

This sense of both international solidarity and astute political awareness within South Wales was not a new phenomenon. Francis (1970) declares that the South Wales Miners Federation for example, had been internationally aware since the end of the First World War and this episode was, ‘a re-emergence of class consciousness, centred on foreign affairs and thus expressing itself in feelings of international class solidarity’. The migrants who had moved into South Wales by their thousands had assisted this internationalism. The coalfield was truly cosmopolitan with people from countries such as Australia, England, France, Ireland and interestingly, given the context of this discussion, from Spain. Most of the latter migrants had started to arrive from northern Spain from 1907 onwards and importantly, they brought with them, republican, socialist, and anarcho-syndicalist political ideas. Unfortunately, during the early years, the migrants did experience some form of bitterness and hostility, which mainly derived from the older generation. As in the cases of many migrants they were perceived as different, a threat, and their Catholicism to some was as an affront to traditional Non-Conformist values. Irish and Italian immigrants had also experienced similar problems and there had been reports of an Italian café being attacked during the Tonypandy riots of 1910 (Williams, 1998: 71-2). However, this hostility gradually faded and the younger generation welcomed them and respected their political values. Given time, it was generally accepted that much of the political and international consciousness had appeared in areas of South Wales not, ‘with the publication of The Miners’ Next Step but with the coming of the Spaniards’ (Francis & Smith, 1998: 10-13).

The conclusion of the First World War witnessed a dramatic sea change within Welsh politics. The coalition government of Lloyd George’s Liberals and the Conservatives was in turmoil at both home and abroad. Increasing unemployment was one factor that led to its increasing unpopularity especially within the industrial south and this ultimately resulted in the growth of the Labour Party (Morgan, 1988: 100-101). Edwin Greening (2006: 16) supports this as he comments, ‘After 1919, the mass of the Welsh people deserted the Liberal party and, from then on, it was the Labour Party that dominated the political life of the Aberdare Valley and Wales’. During 1919, the South Wales Miners Federation (SWMF) called for nationalisation along with reduced hours and increased wages but by 1921, the situation had deteriorated. To give one example of the conditions during this period,within the Cynon Valley, all collieries were by now working part time (Cynon Valley History Society, 2001: 173-4). During the period of 1920 to 1922, membership of theSWMF actually fell from 197,668 (its highest peak) to 87,080 (Williams, 1998: 40). However, those unlucky enough to suffer unemployment decided to fight back and National Hunger Marches to London began in 1922, in an effort to lobby Parliament (Francis & Smith, 1998: 20).

As the 1920s progressed, so did the Labour Party’s political fortunes. It won several by-elections within South Wales during the period of 1919-22 and was steadily increasing its dominance. Indeed, such was the progress it was making within South Wales, it almost, ‘seemed pre-ordained, a simple reflection of the dominant working class character of the social structure of the coalfield’ (Morgan, 1988: 101). At the same time as socialism was taking a firm hold on the coalfield, the Communist Party of Great Britain had also started to build a significant base within the region (Francis & Smith: 28). Thorpe (2000) declares that the Communist membership figure within South Wales in 1922 was 9.7 per cent as opposed to 31.4 per cent in London and 24 per cent in Scotland though the figures have to take into account the vast differences in population between the aforementioned areas. Efforts were made to affiliate the SWMF to the Red International of Labour Unions, which would have signified a move to revolutionary trade unionism. However, unlike its Scottish counterpart, the United Mineworkers of Scotland, the SWMF did not affiliate. Circumstances differed at the time, but there was still little doubt that the South Wales miners had developed an affinity to a ‘proletarian internationalist perspective’ (Francis & Smith: 38-9).

During the mid-1920s, the fires of socialism and communism were burning bright within the Welsh coalfield. Marxist ideas inspired new means and methods of militant industrial action and this was at its peak within the South. This was particularly evident within the Anthracite Strike of 1925 (Francis & Smith: 42). The General Strike and miners’ lock-out of 1926 is another significant part of Welsh history and the dispute gave further proof of the links between the proletariat of South Wales and international Communist organisations. In addition, the Russian trade unions contributed a sum of £1,161,459 2s.6d. to the British Miners’ Relief Fund. During the dispute, the TUC General Council was involved but it was not prepared to deal with the consequences of full-scale industrial action. Unlike the miners, they focused upon conciliation not revolution and as a result, the miners’ actions were ultimately doomed. In November of that year, the dispute ended and the miners had been defeated (Williams, 1998: 23). However, the commitment and consciousness of the miners during the General Strike and lock-out were incredibly strong and a collective solidarity had been forged which had no parallel in other parts of the British coalfield. As the poet, Idris Davies declared, ‘We shall remember 1926, until our blood is dry’ (Francis & Smith: 52-5). Clarence Lloyd, who later volunteered in Spain, gave his assessment overall:

(We were) beaten by deprivation. Lump of bread, corned beef, soup and a couple of spuds (was the) diet from the soup kitchen. (1926 was a) big influence. I became more deeply engrossed in the trials and tribulations of the working class. I was like an animal trapped in a corner. I had to fight. It was a question of survival…The sum of all the people’s struggles resulted in a mass struggle.

(Cited in Francis, 1984: 45)

The miners may have been defeated but there was little doubt that a spirit of defiance and determination had been instilled in them as a collective whole. This would serve useful following the collapse of the strike as unemployment spread like wildfire across the coalfield. The miners were victimised for their actions and blacklisted (Francis, 1984: 46: Williams, 1998: 23) and as a result, ‘They were now unemployed communities rather than colliery communities and were forced into any and every means to defend themselves’ (Francis, 1984: 46).

The post 1926 period was a turbulent time within South Wales. Many miners became totally disillusioned with the South Wales Miners’ Federation and it was blamed for being both powerless and for being culpable for the collapse of the General Strike. Non-unionism increased significantly and a rival union, the South Wales Miners’ Industrial Union (SWMIU) was founded (Williams, 1998: 23). As a consequence, the SWMF decided to re-evaluate matters and a total restructure of the union eventually took place (Williams, 1998: 44). Although the rival SWMIU was supposedly non-political, it was perceived by many of its opponents as being the exact opposite and it was regarded as simply a tool of collusion for the coal owners. In a speech by miners’ leader, A.J.Cook, he declared ‘The Non-Political Union was born in the colliery office, supported with Tory beer, and fed in the Tory clubs, and when the employers withdraw their support from it, it will die’ (Francis & Smith, 1998: 113). The rival union did little however to diminish the international perspective of the SWMF and its philosophy in this area remained unchanged (Francis & Smith, 351).

Although the Labour Party increased its power in both the SWMF and within the industrial valleys, the Communist Party was also exerting its own influence amongst both the employed and unemployed miners (Francis, 1984: 46). By 1927 it had formed thirty-eight branches and had a membership of around 2,300 within the South Wales region. Although it remained in a minority it was regarded as the most active of the political groups and has been described as being, ‘ a contagious minority which charged the south Wales labour movement with power, internationalism, and colour’ (Williams, 1998: 58). Greening (2006: 32) comments on the Communists after the collapse of the 1926 strike:

The TUC and the Labour Party were annoyed at the heroic resistance of the miners and the only people who gave loyal support to the bitter end were the Communist Party of Great Britain and the people of the Soviet Union.

Such support would inevitably have great influence on men like Edwin Greening and he also makes an observation on the situation within his home town of Aberdare in 1932 (43):

Britain then had over three and a half million registered unemployed. Aberdare had over ten thousand, and most of them accepted the situation with pained resignation. My friends and I did not accept the situation and Dai and I looked for further political action to change the position. Only the members of the Communist Party, the National Unemployed Workers’ Movement, and the Independent Labour Party were active. The Labour Party, by far the largest political party in Aberdare, did nothing but meet, talk about the latest resolution and let events dictate this action.

Such political consciousness was never more pronounced than within Mardy in the Rhondda Valley. The town was to develop a unique place within political history for its strong association to Communism (Williams, 1996: 192). Mardy became known as ‘Little Moscow’ after the label was used as an insult by hostile reporters. However to the people of the Mardy, there was a definite sense of pride in such a name (Francis & Smith: 53).

In 1933, a number of political agitators were imprisoned including four South Wales Communist leaders. At the same time, the threat of fascism was beginning to emerge from continental Europe. The way in which the German working class were crushed was a stark reminder to the people of South Wales (Francis, 1984: 61). A new approach was called for so a unified strategy was implemented comprising of both Communists and non-Communists (64). This United Front meant that the Communists were abandoning their traditional policy of non-co-operation with the Labour Party. This was in effect, the creation of a two pronged attack for the sake of the working class (Williams, 1996: 185). The Labour Party were equally guilty of non-co-operation though and had adopted a similar policy back in 1925, when the Labour Party Conference ruled against Communists being allowed to hold dual membership (Francis, 1984: 48). By 1934, the Communist Party had increased its influence so much that it polled over 40,000 votes in local elections and this transferred to an increase in membership by 1935 (Francis, 1984: 66). The last two Hunger Marches in 1934 and 1936 are regarded as the most significant moment of the United Front in practice (Francis & Smith: 245) and they also demonstrated that a working class consciousness was virtually identical to a community consciousness.

With the growth of European anti-fascist movements, miners within South Wales perceived their own struggles in a similar vein. For instance, Will Lloyd (who would later volunteer for the Civil War) from Aberdare stated that, ‘The Powell Duffryn Coal Company is fascism’ whilst the argument over scab labour in Bedwas was compared to Nazi Germany (Francis & Smith: 354).

A number of important and charismatic figures emerge for the Communist Party during this period, namely Arthur Horner, Will Paynter and Lewis Jones, all of the Rhondda. All three were such influential figures; they were a major factor in the success of the Communist Party within the Rhondda Valley (Williams, 1996: 183). Jones was regarded as the champion of the unemployed (Francis & Smith, 1998: 305) and had joined the Communist Party in 1923. He was later blacklisted whilst employed as a Cambrian lodge checkweigher (Francis & Smith: 305). He had been imprisoned during the 1926 lock-out and had also led three Hunger Marches from South Wales to London (Francis, 1984: 102). Jones was advised not to volunteer to go to Spain as he was such a brilliant propagandist and was a tireless worker. Tragically, this was to be his ultimate downfall, as he collapsed and died after addressing over thirty seven meetings in relation to the Spanish Civil War, the very week that Barcelona fell to General Franco in 1939 (Francis & Smith: 354-5). His two fictional novels, Cwmardy (1937) and We Live (1939) were based around his political experiences in the Rhondda (Williams, 1998: 9). In their study of the South Wales Miners, Francis & Smith (1998: 355) pay tribute to Jones and his second novel, We Live. They declare:

We Live vividly illustrates in human and political terms the effect on individual families and the internal and external turmoil of the Communist Party in the South Wales valleys over the Spanish question. In this sense, of all the Welsh writers, it was he who came nearest to describing what ‘Spanish Aid’ really meant.

This ‘Spanish Aid’ varied within the South Wales coalfield. For example, in Glyncorrwg, the South Pit Lodge formed a Spanish Aid Committee, whilst in Abercrave, the Welsh Spaniard migrants of that area persuaded the SWMF to send £100 to the Asturian miners’ families involved in the 1934 rising (Francis & Smith: 352). Aid Committees were also formed in other parts of South Wales including Cardiff, Barry, Talgarth and Swansea and similar committees evolved in the North. However, it is interesting to note that there were claims of anti-Catholic feeling amongst a section of Republican sympathisers within North Wales (Francis, 1984: 122-3).

In relation to the Asturian rising, Welsh writer, Gwyn Thomas, pinpoints it as one of the two defining moments that were pivotal in finally solidifying Welsh support for the Spanish Republican cause. The first was the Gresford colliery disaster in North Wales, in autumn 1934 and secondly, the brutal suppression of the Asturian miners protests by General Francisco Franco and the Spanish army, which developed in Spain a few weeks later. There was widespread anger and revulsion over Gresford. Many people felt that safety regulations had been knowingly contravened which in turn led to the tragic explosion that had such horrific consequences. The miners of South Wales felt outrage over both incidents and identified a link between the tragedy of Gresford and the events of Asturias (BBC Documentary, 1979). These factors allied to the influence of the Communist Party in both direct political action and within the SWMF go a great way to explaining the position of the Welsh response to the Spanish Civil War (Francis & Smith: 351).

In 1935, the miners instigated a new form of direct action with the adaptation of ‘stay-in’ strikes. This was effectively an occupation of the workplace and it was perceived as the only remaining tool of direct action that a battle weary workforce could undertake. (Francis & Smith: 297-8). With it, the miners of South Wales were reinvesting their belief in the SWMF and were attempting to take back control of their lives away from the hands of their capitalist overlords.

With the onset of the Civil War, the first Welshman to offer to volunteer from within Wales was the Reverend Daniel Hughes of Machen, although a couple of Welsh migrants now based elsewhere had preceded him (Francis, 1984: 159). As the war progressed, there was widespread support across Wales. Collections, meetings, and rallies were all in abundance and the Communist Party was more often than not, at the forefront of proceedings. Nevertheless, this influence did not manifest itself in political power. The Labour Party was dominant within the area and had the support of the majority of the miners and their families and no Communist party member was ever elected on a parliamentary basis. As the Second World War approached, the SWMF had a newfound confidence that it had gained because of a decrease in political and industrial hostilities. In 1937, a Wages Agreement was brokered because of the new approach to industrial relations by its president, Arthur Horner. Ironically, despite its lack of political power, Horner was a member of the Communist Party (Williams, 1998: 24).

However, despite all of this, not everyone within Wales sympathised with the Republican cause. One individual miner from South Wales is quoted as saying, ‘Why should they be rushing over to another country to fight when there’s all the fight they wanted here?’ (Hopkins, 1998: 151). In the early part of the 1930s, the British Union of Fascists under the leadership of Oswald Mosley, played upon the problems of poverty and unemployment and in doing so, established branches within areas such as Cardiff, Merthyr Tydfil, and Swansea. Trade Unionists and other political activists within South Wales were quick to mobilise. Fascist meetings in towns like Aberdare, Merthyr and Tonypandy ultimately met with great resistance and were snuffed out. Nevertheless, there were still those within the country who were sympathetic to the fascists and to the cause of Franco in Spain. Indeed, such allegations were often levelled at the then leader of Plaid Genedlaethol Cymru, Saunders Lewis (Footsteps, 1999: Stradling, 2004: 81). Additionally, one Welshman, namely, Frank Thomas, travelled to Spain to fight for Franco and the Nationalists. However, as far as records show, he was the only Welshman to do so (BBC Documentary, 1979; BBC 2 Wales, 2006). Fuelled by a sense of adventure, Thomas joined the Nationalist cause but eventually returned to Wales after being wounded. For Thomas, the appeal of Franco would gradually fade and he later fought against Hitler and the Nazis in the Second World War.

The Welsh academic, Robert Stradling, is one individual who has been particularly critical of the influence and significance of the Welsh volunteers. He published a book, Wales and the Spanish Civil War: The Dragon’s Dearest Cause in 2004 and followed this with a documentary for BBC2 Wales in 2006, where he travelled to Spain along with a Spanish researcher, Anna Marti. Although Stradling recognises that the war ‘was a mosaic of causes’ including political, religious and social factors, he makes great emphasis of the religious causes. He argues that all of Wales should be recognised and not just the miners of the south and this pan Wales interest was actually motivated by Non-Conformist, anti-Catholic prejudice:

But is seems to the present writer that the culture of anti-Catholic (even in some respects, anti-Spanish) feeling was profoundly involved right across alleged geographical and class divisions in Wales.

(2004: 26-7)

He follows this in his documentary by asserting that the Wales of that era was still largely Protestant and the Republican cause in Spain was geared against the Catholic Church (2006). He is also critical of the movement of Spanish refugee children to Wales and claims the need to move refugees was mainly Republican propaganda. He writes, ‘Many who did not share an outright commitment to the Republican cause felt, not without some reason, that the whole affair was a propaganda exercise’ (2004: 44). During the documentary programme, his assistant, Anna Marti is critical of Stradling’s philosophy in relation to the whole conflict. This theory of Welsh volunteers being involved in some form of Protestant religious crusade is highly questionable. For example, in The Colliers Crusade (BBC, 1979), a number of the men interviewed, including Will Paynter, explain how they had turned away from religion, even though they had grown up in a Non-Conformist background. Also, the Basques who also fought on the Republican/Loyalist side were staunchly Catholic. If the Welsh were so anti-Catholic why were they still taking an interest and siding with one half of the equation who encompassed such staunch Catholics as the Basques? As Francis (1984: 187) declares, ‘the Welsh response to Spain was in no way religious, but political’. Two further examples are those of Edwin Greening and Tom Adlam. Greening was an Aberdare volunteer whose sister converted to Catholicism through marriage. In his later years he wrote From Aberdare to Albacete. In his memoirs there is mention of this but there is no reference to anti-Catholicism from either him or anyone else (2006: 45). In The Colliers Crusade (1979), Adlam recounts the story of when he persuaded a disillusioned young Irish volunteer not to give up his Catholic faith. These were hardly the actions of some religious bigot. If there was any argument at all, it was more likely to be against the hierarchy and power of the Spanish Catholic Church, which had been used to practically enslave a large percentage of its people rather than Catholicism itself. As Kent (1986) comments, ‘the war in reality served only to pit Nationalist Catholic against Loyalist Catholic’.

In his review of Stradling’s work, Buchanan (2006) acknowledges that he has attempted to broaden the base of Welsh involvement in the war and in doing so he is opening the debate up for wider discussion. Buchanan also believes that Stradling has correctly questioned certain myths and clichés that arise from the war in relation to Wales. He does feel that there are weaknesses in Stradling’s argument though and he believes that Stradling doesn’t explain the reasons why half of the miners in the British Battalion were men from the South Wales coalfields. Buchanan states that the fact that this statistic exists at all proves that something remarkable was happening in the Welsh coalfields:

In a memorial ceremony to the Welshmen killed fighting for the International Brigades; Arthur Horner read the following extract:

To die is not remarkable or important, for all must die. The matter we have to concern ourselves with is: What did they die for? We are not here mourning our dead. We are here to remember what they died for. In South Wales, we have lived for freedom and we are determined to fight for it, challenged as it is in a hundred different ways at the present time. What we must demonstrate is that we are ready to work tomorrow and the day after against the forces which work to destroy our rights

(Cited in Francis, 1970)

That quotation serves as a fitting tribute to those Welshmen who participated in the conflict. These were not individuals who were conscripted or pursuing a career. These were men who held such strong beliefs and principles, they acted upon them accordingly. In our contemporary world where apathy, selfishness and ignorance often flourish, it is highly questionable whether such actions would ever likely be repeated. It is easy to be cynical and cast aspersions on the levels of support within Wales and the reasoning behind it. The fact of the matter is that solidarity did exist and these men are the proof and they did not volunteer out of religious bigotry. Such claims sully their memory. We must recognise the fact that there had been racial and religious problems within Wales just like there had been across Britain. However, we must also remember that any hostility towards immigrants especially Spanish eventually dissolved and the latter had a great part to play in influencing Welsh political life. By studying the solidarity and the resultant response, we can soon conjure up an effective picture of the political landscape of South Wales. Through their own experiences of industrial struggle and social poverty, the people of South Wales had become highly organised, politicised and indeed, radicalised. Consequently, these were people who understood struggle and suffering. They could empathise with their counterparts in Spain and what better way to show solidarity than by assisting them in their struggle against fascism. As Evans (2000: 95) declares, ‘Enthusiasm for the Republican cause reflected the maturing political consciousness of industrial Wales in the mid-1930s’. Ironically, the British proponents of fascism tried to gain a foothold within the very areas that the volunteers came from but they were beaten back after meeting great resistance. Whilst No Pasaran! was the memorable battle cry of the anti-fascists in Spain, the same was certainly applicable to the people of South Wales and it is notable that just one Welshman fought for Franco during the struggle. South Wales can be justifiably proud but also grateful that they kept the wolf of fascism from the door. Sadly, all the surviving Welsh volunteers from the struggle have now passed away so to them and to those who perished on Spanish soil, Que en Paz Descanse. Their memory lives on.

AGOR (2008) Coalfield Web Materials: Spanish Civil War [online]. Available from: http://www.agor.org.uk/cwm/themes/Life/international_relations/spanish_war.asp [Accessed: 19 March 2011]

BBC Documentary (1979) ‘The Colliers’ Crusade – Wales and The Spanish Civil War’ [online - Video film]. Available from: http://vimeo.com/5478778 [Accessed: 11 April 2011]

BBC 2 Wales (2006) ‘Wales and the Spanish Civil War: Whose History, Whose Legend?’ [TV programme – VHS VIDEO]. Broadcast – 16 July 2006. Available from: University of Glamorgan – Learning Resources Centre [Accessed 15 February 2011]

Buchanan, T. ‘Wales and the Spanish Civil War: The Dragon's Dearest Cause?’ English Historical Review Volume CXXI Issue 493 September 2006 pp.1146-1147.

Cazorla-Sánchez, A. ‘Beyond They Shall Not Pass. How the Experience of Violence Reshaped Political Values in Franco’s Spain’ Journal of ContemporaryHistory, Vol. 40 No. 3 July 2005 pp.503-520.

Cynon Valley History Society (2001) ‘Cynon Coal: History of a Mining Valley’. n.p: Gomer Press

Cynon Valley Leader (2007) Freedom Fighters: Anniversary exhibition takes a close look at Wales’s contribution to the Spanish Civil War. Thursday, August 23. pp.22-23.

Evans, D.G. (2000) ‘A History of Wales 1996-2000’. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

Felstead, R. (1981) ‘No Other Way: Jack Russia and the Spanish Civil War’. Port Talbot: Alun Books.

Footsteps, (1999) ‘Facing up to the Fascists’ [TV programme – VHS VIDEO] BBC 2 Wales. Broadcast – 5 August 1999. Available from: University of Glamorgan – Learning Resources Centre [Accessed 15 February 2011]

Francis, H. ‘Welsh Miners and the Spanish Civil War’ Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 5, No. 3, Popular Fronts (1970), pp. 177-191.

Francis, H. (1984) ‘Miners against Fascism: Wales and the Spanish Civil War’. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

Francis, H. 'Say Nothing and Leave in the Middle of the Night: The Spanish Civil War Revisited', History Workshop Journal 32 (1) (1991), pp.69-76.

Francis, H. & Smith, D. (1998) ‘The Fed: A History of the South Wales Miners in the Twentieth Century’. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

Greening, E. (2006) ‘From Aberdare to Albacete: A Welsh International Brigader’s memoirs of his life’ Torfaen: Warren & Pell.

Hopkins, J.K. (1998) ‘Into the Heart of the Fire: The British in the Spanish Civil War’. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Kent, P.C. ‘The Vatican and the Spanish Civil War’ European History Quarterly, Vol. 16 No. 4. (October 1986) pp.441-464.

Morgan, K.O. (1988) Welsh Politics 1918-1939 inHerbert, T. and Jones, G.E. eds., (1988) ‘Wales between the Wars’ Cardiff: University of Wales Press

Stradling, R. (2004) ‘Wales and the Spanish Civil War: The Dragon’s Dearest Cause?’ Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

Thorpe, A. ‘The Membership of the Communist Party of Great Britain, 1920-1945’ The Historical Journal, Vol.3 No.3. (September 2000) pp.777-800.

Williams, C. (1996) ‘Democratic Rhondda: Politics and society 1885-1951’. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

Williams, C. (1998) ‘Capitalism, Community and Conflict’. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.