Politics and Media Introduction

Politics and Media Main Assessment Content

The following are the unpublished memoirs of Will Lloyd which are reproduced here with the kind permission of his daughter, Gill Malpas. The story is not complete as these are the only memoirs that were in Gill's possession. Nevertheless, they still give an insight into both Will and that particular period of time.

February 1936. After years of turbulent political changes, of revolutionary uprisings followed by periods of repressive dictatorships, in a Spain sharply divided between

.the masters of economic power in the country, led by the army and supported by the church

, on the one side, and the mass of working people organised in a variety of Trade Union and political parties on the other, a fragile Popular Front coalition won a majority of seats in the General Election.

Despite the evident signs of an impending military insurrection, the Government failed to take the necessary steps to preserve its authority. On the 16th of July the threatened revolt began, although the majority of the Army and the powerful Civil Guard, along with the rebel Generals joined together, the expected quick victory did not come.

In the major towns and cities, the workers, almost unarmed but in massive numbers, were unwilling to surrender their newly won electoral power, so attacked the rebellious troops, they took to the streets, erected barricades and confronted the insurgents head on. The Government faced with demands to arm the workers, tried to negotiate with the Generals and when disrespectfully spurned, resigned.

On July 19th a new Government agreed to arm the people, but by this time the Moorish troops of the Colonial Army, transported from North Africa, were already marching on the capital Madrid. Stymied in their hopes of a quick coup, the Generals unleashed total war on the people. The Nazi and Fascist dictators of Germany and Italy immediately gave support and military assistance.

The desperate pleas by the Spanish Republican government for assistance from the European democracies of Britain and France fell on deaf ears. The Parliamentary democracies of Britain and France under the guise of Non - Intervention, quickly moved to a boycott and blockade of the Government.

Help came from the Soviet Union, and more importantly, from thousands of ordinary men and women. They came from countries throughout the world, as far and wide as, France, Britain, Holland, the United States of America and Canada and many more countries. They made their way overcoming personal difficulties and physical endeavour, to stand along their Spanish comrades to serve in the International Brigade.

This is the story on one such man.

IN THE BEGINNING

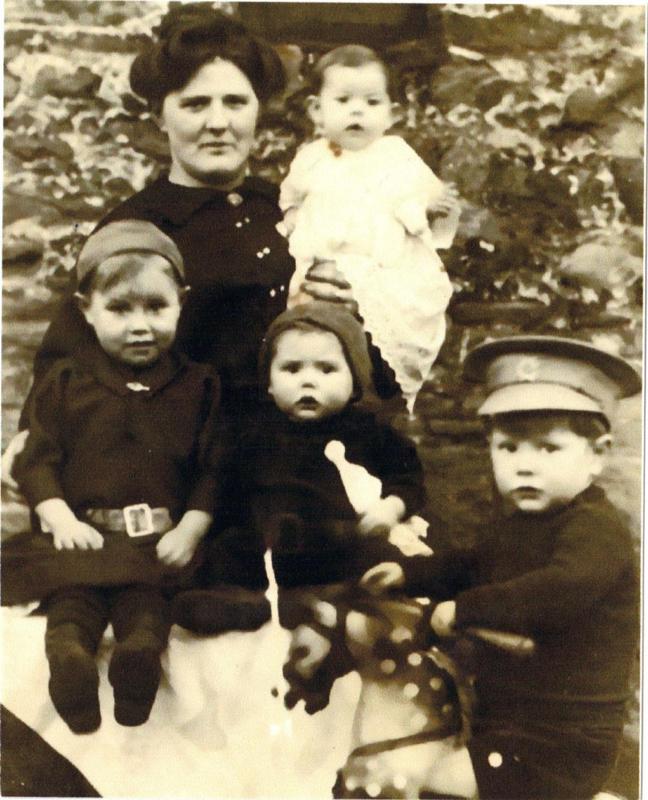

Will Lloyd was born in Aberdare, South Wales in June 1914, shortly before the outbreak of the First World War, the war in which his father would be killed, leaving his mother alone to raise 5 children. In those days of poverty and darkness, Wills mother, known locally as Ma Lloyd, would find the grit and determination to fight tooth and nail for her own version of democracy, namely social equality in the form of food, clothing and health care for her children.

Will joined the Communist Party through the Young Pioneers and remembers his activities during the General Strike. In his own words Will says, I was practically born in the Communist Party, my mother became a member through the Labour Party in the days before Communist were barred. Our house was the headquarters for all the local activities during the General Strike. I took part in the Partys activities in 1926 as a child. I think the first illegal act I took part in was selling photos of the twelve Communist leaders imprisoned for sedition. said Will.

As Edwin Greening who also fought in Spain, wrote in his own memoirs, From Aberdare to Albacete: In the spring of 1934 the Communist Party of Aberdare met at Ma Lloyds house in Cardiff Road, Aberaman, opposite the entrance of Chapel Street. Ma Lloyd was a short, fat, jolly widow. She was about 45 years of age and had five children. Maggie, Iorwerth (who was in the navy), Harold and Will (miners) and Nancy. At the back of Ma Lloyds house was a back kitchen roofed with corrugated zinc sheets. There was a couch, a coke stove, some chairs and a small table. It was small and dreary, and that spring night the only illumination came from a flickering candle in a bottle. Assembled there were Trevor Williams and several other people, including Alistair Wilson, a medical student from Trecynon. In the flickering darkness of that grim room life and communism seemed utterly conspiratorial and exciting. At last, here were people who intended to do something about poverty, unemployment and war.

A BRAVE NEW VENTURE

We were waiting at the platform in Paddington. It was approximately 11.30 pm. I held the package of corned beef covered with brown paper in a position it was bound to be noticed. We waited until the platform was cleared of all London passengers - the platform was now empty. Condon said Where the hell is the contact we were supposed to meet? 'Calm down theres plenty of time, I replied. Then he appeared, walking slowly up the platform carrying the familiar red and yellow jacket of the Left Book Club. He hesitated as he came up to us but walked slowly up the platform, right to the end. I whispered to Condon, Thats him. As he came walking back slowly up the platform, I stepped up to him and enquired if he was looking for a party from South Wales. You could see the shock appear on his face and he exploded. He said I have booked a hotel, I was told there would be forty of you and there are only three! Stop there for a minute, Ill have to go and cancel the hotel. Minutes later he returned, he had managed to cancel the booking but as he stated there was now the problem of accommodating our party. I can put one of you up but dont know where we can find rooms for the other two (Condon and I wanted to stick together).

We left the station and our contact drove round London in the late hours of the night. Then we stopped. He told us to get out, and then led us down steps to a basement. He opened the door and shouted in Can you put these two up for the night? - an affirmative reply, then he was gone leaving Condon and myself gazing around in amazement at a room with no furniture, a few mattresses laid out on the floor, an old wooden box served as a table, the mantelpiece was smothered with the remains of old candle grease with the two candles flickering away. Open mouthed we looked at each other not being able to take it all in, when suddenly a voice Do you want a cup of coffee? We turned slowly and a young man was offering us two tin mugs of coffee. We thanked him and slunk to the floor onto the mattresses, as we slowly sipped the coffee the young man told us there were four of them already staying here, two men and two women - what they called pigging in it. I said that we had to get up early in the morning and as it was about 1.30 am, we would like to get some sleep. At this moment the other three occupants came in from the kitchen. We lay on the mattresses fully clothed and tried to sleep when suddenly the young man who had brought us the coffee said, I know where youre going, youre going to Spain. I replied Where did you get that idea from? He responded with I know and I will be joining you later!

We got up early next morning, said our goodbyes to our hosts and began making our way to our destination in the centre of London; here we met the third member of our squad. We proceeded to King Street, where we were interviewed by a man called Robson. He questioned us closely on our reasons for volunteering to go to Spain. After a thorough discussion he told us to get a weekend ticket to Paris, no passport was required for a weekend trip, but there was a need for secrecy. On no condition, were we to talk to anyone on the train or boat during our journey. We left the office, purchased our weekend tickets and, as the train didnt leave until 8pm that evening; we filled the hours in between in the funfairs of London on the rifle range. We embarked the train at Kings Cross and soon we were off on our first ever journey outside of Britain. It was a corridor train, and whilst walking down the aisle in search of a comfortable seat, I glanced into a compartment which only two people occupied and to my surprise, there was Dave Springhall, a leading member of the Communist Party. He pursed his lips signalling to me not to acknowledge him, so we carried on down the corridor in search of another compartment.

The rest of the journey by train was uneventful, but on the next leg of the journey by boat, and just ten minutes after we had left the port of Newhaven, Condon announced he was going to the bar for a drink. Within five minutes he came back agog with excitement. The bar was full of IRA men going to Spain. We followed him to the bar, and there they were, around 30 of them all drinking away and singing the Soldiers song, the Irish National Anthem! We joined them in a drink and the boat rang with the stories of the Internationals. On arrival at Paris we three said our goodbyes to our new Irish friends and made our way to the Place de Combat.

We left the station and hailed a taxi where we spoke our first words of French Place de Combat I said. The taxi driver raced through the streets of Paris and got us to our destination shortly. When I offered him francs for the fare he refused the money and said Non, non, Salude Comrades, my first experience of international working class solidarity in a foreign land.

Place de Combat was a huge building and to my amazement it was a hive of activity. Hundreds of men lined up outside the building and on the inside were rows and rows of seats packed with men of all nationalities waiting to be sent to Spain to fight for the democratically elected Spanish government.

Eventually, over an hour later, when Condon and I had been interviewed and given railway tickets, we were told to present ourselves at the Gard du Norde railway station at 10 pm that night. It was now around 11am, the thing to do was have a god meal and a few hours rest, because on the journey so far there had been little time for sleep.

We chose a little restaurant down a side street. We sat at a table and wondered how to communicate our needs to the waitress who stood waiting patiently for our order. Condon looked at me and shrugged his shoulders, the suddenly he said I have it. Lend me a pencil. He took the pencil turned to the waitress and made motions of writing, she smiled and nodded, went behind the counter and brought back a sheet if note paper. He drew a pig on the paper then looking straight at the woman, he put his thumbs in his ears and screeched

. Cock a doodle doo.

We got our bacon and eggs, after the waitress had recovered from a fit of giggling. As we tucked in a man came into the cafι, stood at the counter drinking a cup of coffee and chatting to the waitress. She appeared to be relating to him our method of ordering a meal because they were having an amusing conversation, glancing over at us now and then as we tucked in to our food. When we had finished, I lit a cigarette and said to Condon, Well thats the first hurdle over, now what we need is a few hours sleep. Bob, flushed with the success of getting our bacon and eggs said, Leave it to me. He beckoned the waitress, and then tried to explain to her that we needed a bed for a few hours. Bobs antics caused her to double up with laughter but- alas - no comprehension. She returned to her companion at the counter and once again appeared to be telling him of the antics of these two foreigners. Her companion was a tall, slim Breton with the usual black beret, which we were used to seeing on the Breton onion sellers who visited the South Wales valleys. Once they had stopped giggling, he approached our table. Me speak English - good morning, alas as we were soon to learn, that was the extent of his grasp of the English language.

Bob, encouraged by someone who could at least say good morning in English, then really went to town. Putting his two hands together, he placed them at the side of his face, bowing his head to the table in a sleeping motion. He then pointed at himself, then me, then at the Breton. The Bretons eyes shot up! He backed away saying Non, non, then came a stream of French invective from which we gathered he thought we were a pair of Angleterre queers who wanted to sleep with him! I tried in vain to placate him; eventually we paid our bill and slunk out sheepishly onto the streets of Paris.

We abandoned the idea of trying to get a few hours sleep and instead wandered the street of Paris until it was time to head off to the Gare du Nord station. When we arrived at the platform the train was already packed. We stood there wide eyed; it was a scene reminiscent of those I had seen in films of the First World War.

The whole train was full of volunteers going to Spain. Hundreds of Frenchwomen tearfully saying their goodbyes to their men - but this was before the treachery of Non - Intervention by the British and French governments. Threading our way through the train corridors we eventually met up with the Irish boys we had met on the boat while crossing the Channel. We stayed with them until we reached our destination, which was Figueres, a frontier town on the Spanish border.

After leaving the train, we were taken by lorry to an old fortress where, after a welcome meal, we found ourselves in a huge hall. Here the commandant of the fortress welcomed all volunteers who had come to the assistance of the Spanish government. As each nationality was welcomed their national anthem was played, as each anthem was played we stood - in fact we were on our feet more than we were sat down.

We were then taken to a hall where around 50 iron cots were lined around the walls, and told this was where we would sleep for the night. From the time we had left London Bob and I had practically no sleep, so I suggested to Bob we should try to recoup on our sleep immediately. It was around 4 in the afternoon, and it was not long before we were in a deep sleep, but that short nap was noisily interrupted by shouts from a number of IRA boys, when one of their number came in shouting excitedly, They have arrested P

.. As the Irishmen rose to their feet and rushed to the exit, the leader of the group, Frank Ryan, tried to bar their way to the door. They were having none of it!

It was only the appearance at the door, of the small commandant brandishing a revolver which he fired into the air that brought a halt to the commotion. Only after Frank Ryan spoke to the group for a short while, did they agree to await the outcome of the incident till the following morning. So peace reigned, and we had a good nights sleep.

In the morning P

. came into the sleeping quarters and told his story, it appeared he had been in a brawl with a Mexican in a bar, the Mexican had drawn a knife on him. Both men were arrested and had spent an uncomfortable night in the cold cells. It had been the first shot that I had heard in the country where we had volunteered to help fight for the democratic rights of people to elect their own government.

After breakfast we boarded lorries which transferred us to Barcelona. When we arrived we marched through the city

. and received a tremendously warm reception from the citizens of Barcelona

..to the railway station, where a train was waiting to take us to our base at Albacete. Once again the train was packed full with around 500 volunteers. The coaches on the train were unlike the British enclosed compartments, they resembled huge horse boxes with wooden seats along one side, leaving a small aisle on the right. Condon and I met up with a couple of the Irish boys, where we sat tightly packed, facing the engine.

The train left the station and we sat back enjoying the scenery. On the left the Mediterranean coast and on the other side, olive groves. I noticed the trucks travelling the tracks were filled with oranges. Coming from an industrial coal valley of South Wales, where all our trucks carried black coal, I found the contrast of trucks filled with golden oranges intriguing and fascinating.

As the journey proceeded the inevitable exchange of individual experiences filled the coach. Sitting immediately in front of us, their backs to us were a group being held spellbound by the tales of the sexual exploits of a large bearded man who was, as he boasted, a Bohemian. He was relating a story of meeting a prostitute in Paris and was luridly sharing all the details, interspersed with the fucks and other juicy expressions of sex.

Suddenly, Mick Lehone, one of the new Irish friends we had made, stood up, white faced with temper and screamed at the big ginger man.... You want to wash your filthy mouth out. There followed a long embarrassed silence which was broken by the ginger man, who initially stood up to confront Mick but saw the size of him, then murmured, I didnt mean any harm, and promptly sat down. He carried on with his story but the language was noticeably muted. Here was an example of the contrast between the men who came to fight Franco. Both were sincere but came from different worlds - the Bohemian and the Catholic.

After a long tiring journey we arrived at Albacete where once again we marched through the streets to the acclamation of the people of that city. We arrived at a large barracks where we went through the ritual of welcome and the national anthem of all the volunteers. Immediately following this we were put into different sections; English, Irish and Welsh were put on lorries and sent to a little village outside Albacete called Madrigueras where we were to be trained ready for the Front.

Madrigueras was a tiny village of about 100 inhabitants, a typical Spanish scene. An imposing high church tower which seemed to dominate all around it, a village pump and a small cantina. My first impression was of stepping back a century in time, the donkeys, and the women washing clothes in the river all added to this notion. We were put through our paces with route marches, mock war exercise in the grape vines, with wooden stakes as our rifles.

Our first Company Commander was a man we called Captain Nathan, he had the calm, cool efficiency that marked him out as a capable leader. We complained about the lack of weapons to practice with after a week of exercise meetings. We were told we were to be issued with rifles. Excitement ran high

. that is until we were presented with them

.they were 57 year old Austrian rifles dated 1880! Me, I was thrilled, but the others with more experience of soldiering expressed their disgust. However nothing could be done about it, so I set out clean the rusty barrel of my rifle and make into a suitable weapon.

As the days went by we became a company of soldiers with different religions, different backgrounds, even differences in political viewpoints. This became evident when we had an incident with one of our new found comrades who was a sailor from Cardiff. Pat Murphy tried to insist on setting up Soldiers Councils. I remember the arguments raging over this.

Captain Nathan put his point - accepted by the majority of volunteers - it was that we had come out to assist the Spanish Government not to impose our ideas on the organisation of the army. We would put ourselves at the disposal of the command of the Spanish Army.

After a short period we were told to prepare ourselves for the Front, we were to join a French Battalion, the 12th Battalion of the International Brigade. We were on our way to the Front.

We arrived by train and were outside the station when an aeroplane appeared and started machine gunning the station. We dived for cover and fired back. He dived at us. He made two runs but I think the fire from the 1st Company scared him off, he flew away much to my relief.

As we marched through the town we could see a procession of refugees who had fled from the Fascists. A young Spaniard beckoned me and showed me a number of women who had had their heads shaved off by the Fascists.

We marched out of town to meet up with the 12th Battalion under the command of De Lascelles, a Frenchman who looked every inch of his six foot, a soldier. We took up positions on the hill amid the olive trees which seemed to stretch endlessly in every direction you looked. Our objective was a little town called Lopera in the Cordova province. Nathan led the attack but as we raced down the hill approaching the village a man appeared, he was screaming Go back, go back. He and Nathan exchanged a few angry words, but we retreated, back to the crest of the hill. While I was not in a position to know all the facts, according to the stories which usually infiltrate the ranks, it appears that it was a trap, and the French Battalion who were supposed to attack on our flank, had not moved.

We dug in under the olive trees, each of us digging a shallow trench just deep enough to lay down in. I was awoken next morning by the sound of voices raised in anger, when I looked around De Lascelles was going around the olive trees and kicking the men awake. A few Scots Brigadiers were reacting violently to this treatment and raising their rifles in readiness to shoot the French Commander. Only the intervention of soldier who had warned Nathan of the trap at Lopera averted a very ugly situation. This soldier was Jock Cunningham. He had formed the company with a few other British who had been fighting in Madrid. Among them was Cornford, the student poet who was killed on the front at Lopera.

The company assembled following the incident with the French Commandant and marched down the road. There he addressed the whole Battalion informing us we had to take up fresh positions. On this Front a few strange things happened. Grenades without powder, the failure of the bulk of the French Battalion to support the attack and the mysterious death of Ralph Fox, Daily Worker Correspondent, behind our own lines.

When we arrived at our new position, the No.1. Company sent out two patrols to scout out the area. I was picked to go on one of the patrols in company with Prendergast and two more Irish lads. We proceeded through the olive trees and I remembered having an argument with Prendergast as to which was east, west, north and south. I told him the sun rose in the east therefore the way we were proceeding with the sun at our back, we were obviously going west.

We eventually reached the top of the hill, when out of the blue a voice shouted at me, By God Lloydy, I was just going to shoot you down. We had met the other patrol. We joined forces, and then suddenly we heard a few shots down in the valley. We cautiously approached the place the shots had come from and saw a group of French soldiers surrounding a tree. A man jumped out of the tree and the Frenchmen pounced on him, beating him with their rifle butts. They gave him a terrible hammering and if we had not intervened I am sure they would have killed him. We suggested that if their story of catching him signalling to the enemy was true, they had better take him back to their battalion for questioning. Reluctantly they agreed and carried him back. We, the first No.1 Company patrol, returned to reiterate what had happened.

Later that day Captain Nathan called us together as said there was to be a field Court Martial and we were to select two delegates to attend. The delegates later reported to the Company that the Court Martial was for De Lasalle, the French Commander. He was accused of treachery and of being a spy. He was sentenced to death and was offered a revolver by the chairman of the Court Martial, which I was told was customary, that he should be offered a choice of honourable suicide. He refused the offer and the Chairman of the Court Martial shot him himself.

The following day we were told we had been ordered to Madrid, after two days of travelling by lorry we arrived at Madrid, still a company with the French Battalion. While on the outskirts we came into contact with the Garibaldi Battalion. Italian, most of them, exiled or escaped from the Fascist Dictator, Mussolini. All wore red neckerchiefs.

We were in an attack when one of the old horror stories that had been implanted in my mind, the one about Italians putting up their arms in surrender, was shattered. They fought in an attack with tremendous courage. We were being attacked on the crest of a hill overlooking a small town. We were in reserve. Now, I had been given a French shosser automatic gun and a new man to join our company was my second. His job was to fill the half-moon clips of the automatic rifle. I stood the rifle on its tripod. At that moment we couldntt establish where the fire was coming from. I remember Nathan, who was standing along the line of the company, being told by one of the men, There is a sniper firing at us. He looked straight into the complainants eyes and said Go and tell him to stop it then.

Minutes after this witty repartee a bullet whizzed past me - how I dont know. It killed my second, an ex-guardsman who stood six foot. I heard a thud and turned in time to catch his last breath. How the bullet missed me is a mystery. I was lying on my side in front of him. Jock Cunningham came running up, a quick glance then he said Hes dead.

Later we moved to new positions, moving mostly by night, I well remember the bitterly cold nights. I woke up one morning, and my hands, which I had kept outside the coat, were frozen solid to the cloth.

Travelling one night from one position to another I managed to collect four discarded rifles, I was carrying five rifles when Campeau, a section leader brought Cunninghams attention to the incident. That was the beginning of a real comradeship between us both. This, and a number of other tasks I carried out without prompting, such as going back to find out why the cookhouse had not sent our food on time.

I remember going back looking for the lorry which should have brought our food - it was a pitch black night. As I walked down a sandy ravine I saw a man lying on a stretcher, there were two doctors operating on him, they called me over and indicated that I should hold the flashlight. I held the flashlight while the doctors split the skin above the mans eyebrow and slowly manipulated a bullet from his head. When they had finished bandaging him, one of the doctors turned and thanked me while pressing a small tin of cooked ham into my hand. I thanked them and continued on my way still looking for our lost cookhouse, but at least the situation was not so desperate now, at least I had a tin of cooked ham.

Later, news seeped through the ranks that we were going back to Madrigueras to join a newly formed British Battalion, were put on lorries and made our journey back. Within half a mile of our destination we were told to get off the transport and line up in formation, thus we walked proudly back to the base where a remarkable welcome awaited us, even though we looked like a bunch of brigands, unshaven, a motley crew, each man with his own particular brand of headgear and uniform.

A Trade Union Delegation from Great Britain was introduced to the men as they lined up on parade. Then a slap-up meal. Fresh boiled eggs, tea, bread and butter, all without a whiff of garlic! After our meal a good clean up and change of uniform. Many of the men were loath to part with the souvenirs, such as German helmets, peaked caps, and the leather jackets they had acquired during their days on the front.

The following day we had the opportunity to meet the new members of the British Battalion, a large group of Welshmen who were instinctively drawn to. They had many questions; How was the fighting? What was the situation at the Front? Alas, as ordinary soldiers the only questions we could answer were those of our own personal experiences. Most of the information about the state of the war - we - as any others had to, depended on the newspapers for the latest news.

That same day we were told that as a special treat the No.1 Company would spend a day in Albacete. So two day later I found myself on a truck with other volunteers, on our way into the town. When we arrived and got off the truck, Campeau informed us we should be back at this position at 9 pm because there was a blackout. We were then free to go our separate ways and seek our individual pleasures.

I paired off with a Liverpool lad called Stevens; he was a well built and hefty young man. We found a cantina in the market place where we ate and drunk, and then speculated as to what to do next. The obvious thing for a young soldier retuning from war was to look for a woman. Unfortunately for us, but probably morally right, the Spanish Government had closed all brothels. As we sat supping our drinks and discussing the dilemma of what we should do next, a tall blonde man approached us.

He said Youre British arent you? We both nodded our agreement. He then sat at our table and told us he was a Finn, a merchant seaman who had jumped ship at Malaga and had come to Albacete to join the International Brigade. We told him we had been to the Front and had been given a rare days leave. He laughed and said he had guessed as much. I have been watching you, and Ill bet I know what you want next, and thatll be a woman. I have been here a few times he continued, and I know a place if youre interested. Stevens and I were of one accord, We sure are we agreed. Well lets go was his reply.

We stepped out into the night and he led us up a narrow side street, stopped at a door and knocked. Suddenly a small slot in the door opened, only a pair of eyes could be seen. The Finn uttered Malaga, and the door opened. Once inside we followed him through the corridor into a very small room with bare walls and a floor strewn with sand. There were also three round tables and six chairs. We all sat at the table and the Finn turned to the old man who had let us in to the building and repeated the word Malaga. The old man shuffled out of the room and returned with a bottle of Malaga wine and three glasses, I went to my pocket to pay. The Finn said, No, you pay at the end.

He told us that the old man, who had now seated himself at a table near the door, was a German, as was his wife. He looked very old and scruffy as he sat silently at the entrance.

We had finished the bottle of Malaga when abruptly our Finn said I have to go now and report to barracks, you just sit here quietly and take your time with the wine. With that he left us and went on his way.

We asked the old man for another bottle, slowly we drank our wine, glancing every five minutes at the door eagerly awaiting the appearance of a beautiful Spanish senorita!

By this time I felt the need to use the lavatory. I approached the old German and by making the appropriate gestures he comprehended my needs. He took me into the corridor and pointed to the back of the building. As I made my way along the unfamiliar abode, I inadvertently opened a door which led into a kitchen; there a buxom woman was cooking, of all things, a meal of egg and chips! I pointed to the food and indicated my delight, and somehow managed to order egg and chips for two. Her response was Si si hombre

pronto. So after unloading some of the Malaga wine took two plates of egg and chips into the room where Stevens and the old German were sitting.

After the meal, which was tinted with garlic, and tasted wonderful, we ordered yet another bottle of Malaga. Stevens, obviously becoming impatient said to me Where the hell is this bit of c**t we were promised? 'Ask the old man, I said. You ask him he retorted. In the midst of this wrangling, in she came! She was young, around 18 years of age, very attractive and dressed in the manner of a traditional Spanish dancer. She looked around the room, and promptly left. We looked at each other, Stevens and I. That must be it! But how do we go about it?

By this time I had become fuzzily drunk on the sweet Malaga wine, and we returned to the question of How do we go about it? and who was going to ask the old German. Eventually, I went over to the silent old man and said C**t? and pointed at the doorway through which the young girl had disappeared. Si si, he replied. I pointed to myself and nodded at the door. Again he replied Si si. So off I went, down the corridor, where earlier I had ordered egg and chips, the buxom cook was still there and after a brief exchange she pointed to a door. I walked through the door and up the stairs to a landing, walked through another door where at once, a hand went to my trousers, whipped put my manhood and washed it in a basin of fluid. After the wash, the woman held out her hand for a tip. She was an old crone of a woman, just like the witch of Cowdor! But I gave her a tip. She then disappeared through the door. I turned then to assimilate the darkened room, and there she was, lying sideways on the bed, still with her shoes and stockings on, but the top of her stockings to her naval was bare. The shock of seeing her stretched out cold with her c**t so brazenly exposed almost put me off completely. Still woozy with drink I decided that as I had come this far I should complete my mission. I dropped my trouser and slowly lowered myself on to her in the hope of regaining some semblance of sexual stimulus. I attempted a grope at her breasts, her response was, Nada, nada. I lay there but was completely turned off and said to her Mala, mala. She asked if it was her but ever the gentleman, I said no, it wasnt her. I stood up, fixed my trousers, paid her and left.

I returned to the downstairs room where Stevens was anxiously awaiting his turn. How was it? he asked. Just great I replied. And off he went. As I sat there sipping the Malaga wine and waiting for Stevens to return, I began to wonder what was wrong with me. I had heard many men talking about the pleasure of sex with these prostitutes but the sight of it exposed like a lump of cold meat left me cold and made me feel sick. My thoughts were, you may as well buy a lump of steak, wrap it around you p***k and masturbate. These thoughts were interrupted by the return of Stevens who had a huge grin on his face

..he had obviously enjoyed himself! We ordered another bottle and talked about it. I lied to him and said I had given her the works, his was practically the same story. Now, we were warriors, who had sated their sexual appetite as men should. Well, I said, its time to go. Stevens agreed. We beckoned to the German who had sat there silently throughout, I asked him for the bill in my limited Spanish. He went back to the table, totted up on a little slip of paper and presented us with the bill. I asked Stevens how much money he had left, and then counted out all my money; we were about 20 pesetas short. How were we to overcome this dilemma? We whispered to each other, of course there was no need, the silent German couldnt understand English anyway - and again it was I who had to explain our position. So, I gathered all the money we had went over to the table where he sat and handing the money over said No dinero. Pointing to myself I told him I would go and see Capitan and bring money back. Silence! A frown appeared on his face as he slowly thought it over, then he beckoned me to the door, as he was opening the door to let me out, Stevens appeared behind. He turned to Stevens saying Nada, nada. Whilst gesturing for him to go back in the house. Stevens caught hold of him, thrust him to one side and we both raced up the road to the square at Albacete. When we recovered our breath, we had a good laugh about the incident. It was now nearing 8.30 pm; we had no money so the only thing to do was to make our way to the picking up point where transport would be waiting for us. We got there about three minutes to nine, we had been drinking almost all day and the Malaga wine had been sweet, but very potent.

The lorry was standing there waiting when Campeau, the section leader turned to me and said, Lloyd, some of your men are late, will you go round them up? I agreed and went up the main street of Albacete and into the cantina, saw some of the boys and told them to get back to the lorry. By now the full effects of the wine began to take effect. I found myself in some posh place where there was a beautiful blonde; I sat in a chair opposite her open mouthed. It was like a dream.

The next thing I remember was getting back to the pick-up point where to my amazement, there was no lorry. They had gone without me! I stood there befuddled with drink wondering what to do. Suddenly, without rhyme or reason I found myself walking into the Grand Hotel Albacete. It was a huge restaurant with enormous crystal chandeliers hanging from the ceiling. I passed the two uniformed guards and walked up the stairs to the main hall. It was a massive place, the only light coming from a door which led to the kitchens. All lights in the halls were muted to conform to the blackout regulations.

I sat down at a table near the entrance of the building, there were only two other diners, a young couple at the lower end of the hall. I had barely sat down when a waiter placed the first course on the table. I drank my soup and poured myself a glass of wine from the bottle on the table. Pretty soon the next course arrived and was silently slid towards me. I took another glass of wine and slowly savoured my meal. The young couple from the lower end of the restaurant past me and left the building. Now, I was the only person left in the room which must have held around 300 tables.

Halfway through the meal, the red wine bottle was empty. A lone waiter stood at the end of the hall with a napkin over his arm. Now and again he would walk into the kitchen to talk to someone; the first time he did this I exchanged my empty bottle for a full one from the adjoining table. The waiter then came to my table with the final course, I could tell by his expression he wanted to hurry it up. He returned to his position by the kitchen door which I estimated was about 20 yards away. As I toyed with the food before me it suddenly struck me, I had no money to pay for this lavish meal. It sounds strange, but until that moment I had not thought of money at all. I was still in a very intoxicated state, and now also in a state of panic.

My Spanish was not good enough to explain my predicament, so I wrote my name and Battalion number on a slip of paper and placed it under the plate. I waited until the waiter went into the kitchen and made a bolt for the exit. As I ran down the stairs the waiter saw me and shouted, the two uniformed guards crossed their rifles in an attempt to stop me, but I avoided them. I ran down the road and was chased by the two guards and the waiter, when a French Officer pulled his revolver on me. I knocked his arm down but the guards caught up and pummeled me against the wall with their bayonets. They marched me back to the restaurant and put me back at the table I had been sitting at earlier. The four of them, three Spaniards and one Frenchman were all shouting and blustering at me. Amid all this commotion all I can remember is saying repeatedly F**k you, f**k you.

Suddenly a voice broke in to the uproar and spoke to the French officer, he then addressed me and said You bloody Limeys think you own the world, Ill pay for your meal. By then all common sense had flow, I replied with F**k you, I dont want you to pay for my meal. At that he said to the Spanish guards, Take him away.

They marched me out of the restaurant, down the street, and into a dark building. After a whispered conversation with a man at the door they left and returned to their duties. The man at the door indicated I should follow him. We climbed some stairs, stopped at a door on the landing when he gestured to me that I should stay where I was and he entered the room. About five minutes elapsed before he came out and ushered me into a dimly lit room, a candle flickering on the mantelpiece, there was another man sitting at a small round table. Without turning he said in halting English. What have you to say for yourself? Still brash and cocky I replied, Some of you people should go to the Front line and do a bit of fighting. At that moment he turned full face towards me and I could see that his left arm was severed at the elbow. He pointed with his right arm, without saying a word. I suddenly broke down crying and said I am sorry. He was looking at me, his voice low and cold, when he said, Three days in prison.

I was very anxious to get out of that room. I had made a fool of myself and realised I deserved the punishment I had been given, if only for the thoughtless, insensitivity I had shown. The soldier, who had taken me up, then led me down some stairs. He spoke to another soldier who then took a key from his belt and opened a door. He motioned with a nod of his head that I should enter the room. I walked past him down a short flight of steps into a large unlit room where a number of double bunks were spaced around the room. I sat on a bunk and looked around to take stock of the situation. At the far end a group of men were gathered, they were debating some question in French. I picked up a few words but wasnt paying much attention to them when a man approached me with a torch and a piece of paper in his hand. As he walked toward me he said. Angleterre? I nodded, and then he pointed to the paper and said Escriba. I gathered they were making up a petition, so I signed the paper, whereupon one slapped me on the shoulder and said, Bravo, then returned to his group.

I lay down on my bunk, my mind slowly playing out the evenings events as I slowly sobered up. I realised what a fool I had made of myself and was deep in thought when there was a startling, sharp rattle of keys in the door. It was abruptly thrown open and a small man tripped and stumbled down the stairs into the cell. He sat on his behind for a few moments as the iron door above clanged noisily shut. He rose unsteadily to his feet; he was a small, thin wiry little man. He staggered over to the French group at the end of the room talking loudly in French. I could gather, from my imperfect French and his actions that he was complaining stridently that he was an anti-fascist and he was put in prison by the people who had come to Spain to fight.

Suddenly, the leader of the French group stood up, turning to the newcomer and indicating himself he announced, I Fascist, - you anti-fascist - you no fascist? With that the whole group rose, surrounded the little man, tied a scarf around his neck, and went through the motions of hanging him. The little man was terrified whereupon the group released him - all hugely enjoying the joke.

They talked for a few minutes, then one of the Frenchmen pointed to my bunk and propelled the little man toward me saying, Angleterre. He walked over to me and asked in English if I was. I nodded. He told me he was Irish, had gone to France in the Great War, 1914 -1918, married a French woman and had lived in France ever since. After we had exchanged these confidences he said, What are you in for?

Sensing that the others had had a little fun with him, I thought, now I will have my own little bit of fun with him. Murder, I said. He leapt from the foot of the bunk! Still drunk he staggered a yard or so away, turned back and said, What happened? I told him I had been in the Front line and a Spanish cook wouldnt give me enough to eat, so I stabbed him. Im being sent to Valencia for trial. He took it all in then said, You are a silly boy. If I can do anything for you I will, do you want me to get in touch with your parents? No point I said, Ill get out of it somehow. He pondered this for a moment, and then went over to the other side of the room to the Frenchmen. After a conversation with them, they must have cottoned on to the game, he came back to my bunk, full of sympathy saying Anything I can do, I will. I could see now that I really had convinced him that I was a murderer.

He had sat himself at the foot of my bunk; he was carrying a knife in his belt. These knives were the first thing the volunteers had bought on their arrival in Spain. They were made of Toledo steel, shaped like a dagger and sheathed in a gaudy metal case. I sat up and whispered to him, There is one thing you could do for me. Whats that? he whispered back. Give me your knife, there will only be two guards taking me to Valencia, with that knife I could soon get rid of them. He shot off the bunk saying, No, no, that would be silly, and took himself off to the far side of the room. I sat there smothering a fit of the giggling. After a short while a voice bellowed something which I gathered was, all to bed, no more talking, the voice then told the little Irishman to take the bunk above my head, but the little man wasnt having any of that, and found himself an empty bunk on the far side of the room.

As I lay there, the whole cell now quiet, only the snores of the inmates disturbed the silence, I was musing over the joke I had pulled on the Irishman and now realising what a mess I had got myself into. I didnt sleep until the early hours of the morning.

At last I dozed off only to be hastily awakened by the clang of the cell door. Two guards came down the steps carrying a pot of steaming stew, shouting in French our equivalent of, Wakey wakey. I leapt off my bed, grabbed my tin plate and was the first in line. The guard ladled out of the pot onto my plate when astonishingly, a Frenchman came racing across the room and kicked the plate of soup out of my hand. I turned, ready to have a go at him to be faced with the entire group chanting, No Mange, no Mange! The Irishman walked toward me and asked if I had signed any papers, I said I had. He explained to me that I had signed a petition which said I was on hunger strike along with the rest of the prisoners, in protest over the conditions of the so - called prison.

I asked the Irishman to convey my apologies to the group and to tell them I would join them in the hunger strike. So with chants of, No Mange, no Mange ringing in their ears the guards retired, taking their soup with them.

I retired ravenous to my bunk, and for the first time looked at my prison in daylight. At the highest elevation of the wall were gratings about four inches wide, they continued along all four sides of the cell. From there we could see the feet of people passing to and fro on the street above. We were obviously in a basement which was level with the pavement outside. I was thankful it wasnt raining because it was evident if it did rain, the water would have poured into the cell through the gratings.

There were about 14 double bunks in the cell. There was nothing to do, no books to read, no stimulation, no conversation, well only the occasional few words from the Irishman who was very wary of speaking to me anyway, and except from two occasions, stayed well clear of me.

By around 6pm, when I was well and truly famished, one of the Frenchmen rapped on the cell door and handed the guard some money. To my amazement the guard returned some twenty minutes later and handed the man a parcel of food!

I had no money, so effectively the hunger strike was being carried out by me and a few others unfortunate enough to be as impoverished as I. Deep into the night the cell door opened once again and an officer entered and held a short meeting with the leader of the French group. I was later told by my Irish mate that the complaints had been sent to Andre Marty, and he agreed to investigate them. With that assurance the French agreed to call off the hunger strike. It was far too late now to expect any food, but in the morning, when food did arrive, I really enjoyed the breakfast.

Without any hope of stimulation or distraction, I lay on my bunk listening to the French chatting, with only the occasional laugh at some joker in their pack punctuating the monotony. Around 4pm the cell door opened, the usual guard walked down the steps to the cell with a paper in his hand and proceeded to shout out names. I wasnt very interested

..until my little Irish friend rushed over to my bunk excitedly and said, Thats you, they called your name. It cant be me, Ive got another day to go, I replied. However he insisted so I went over to the guard and asked if I could look at his list, and sure enough, there was my name. I returned to my bed to collect my tunic, and as I did so my Irish comrade came and shook my hand. He expressed his sympathies and asked if he could write to my parents and inform them of my situation. With still a perverse sense of humour I gestured to take his knife. He stepped back striking his head, in a gesture which implied he gave up on me!

I was led to the room in which I been arrested. The same officer was there. I apologised for the trouble and remarks I had made. He shrugged and said Borracho, drunk in Spanish, he shook my hand and handed me some money. I was taken to a door which led to the streets of Albacete.

As I walked along the street I felt grubby and dirty. I had grown a straggly beard and must have looked a right mess. I decided to go to a barber. I chose one of the numerous barber shops, sat down in the chair and the Spanish barber enquired my requirements. I just said the works, and pointed to my hair and head. He started with a shampoo, after the shampoo a haircut. Then he began to lather my face for the shave. I was lying back in the chair thoroughly enjoying the experience when I recalled the first lecture we had had on arrival in Albacete, Never go into a barbers alone. A few men had had their throats cut by barbers sympathetic to the Franco Fascist. With that the razor started to slide down my cheek and my chin sank protectively into my chest. However things turned out alright and I left the barbers feeling like a new man.

Walking along the street, I looked across the road and saw Jock Cunningham, the Company Commander. As I walked towards him a big smile appeared on his face. He told me he had been sent by the Battalion to get me out of prison. I then related to him what had happened. Right, he said, Well go back to the Grand Hotel and apologise to the waiter there. We walked into the hotel and a waiter came to take our order, the very same one that had served me on the night I was arrested. I apologised and offered him the money to pay my bill. He declined and said, Salude Comrade, which was his way of telling me all was forgiven.

Then back to Madrigueras, our base. I spent the following days on route marches and trying out new weapons - which were Russian rifles.

Then an unpleasant incident occurred, the Irish boys we had met on our way to Spain were refusing to serve under the officer appointed to lead the British Battalion. They claimed he had been a member of the Black and Tans fighting the Irish people. A meeting was called by Andre Marty, Leader of the Brigade which resulted in a near riot, with the Irish boys taking over the building and threatening to use their arms in defence of the appointment of this officer. However through the intervention of Frank Ryan the situation was peaceably patched up and finally resolved when, the officer in question had an accident with a revolver and was shot in the leg.

Now the British Battalion was in being and led by Tom Wintringham. At this time we were billeted in a school room. I had been suffering badly with pain from two bottom teeth, my face was swollen and I was unable to eat solid food, the village women came to see me and made a concoction of milk and eggs which was all I could manage to swallow. One day a young Spaniard told me a doctor could take my teeth out, I hurried to the designated place only to find that the doctor, was in fact a vet! He took a look at the teeth and said he was unable to do anything for me. Just then a medical orderly with the Red Cross armband entered the room, he was a young German boy and he offered to take my teeth out. I put back my head, in went the forceps and rather than remove it, he crushed the tooth into the gum. I reeled with pain, knocked his arm back and held my head in my hands. He wanted to try again, and I allowed him, only to be subjected to more of the same, the second tooth was also crushed in to the gum. I rose from the chair, pushed him roughly out of the way, stormed out of the vets surgery and returned to the billet.

I lay for two days in agony, my face inflamed and swollen, when we were told we were going to the Front, and had to load the lorries. Cunningham noticed the scarf around my mouth and asked me what the problem was, when I removed the scarf and he could see what a state I was in he said, Get in with the driver, sit in the cab. I wasnt there long before another Company Commander ordered me out. I spent the whole journey in the back of an open lorry. We finally arrived at a small village called Morata, where once again the schools had been commandeered as sleeping quarters.

Early next morning as we lined up on parade ready to go to the Front, down the line came a Doctor Bradshaw, he took one look at my face and told me to fall out. As the Battalion moved off there were three of us left? We were told to board a lorry which took us to a small castle which was going to be used as a clearing station for casualties from the Front. When we arrived we saw there were four medical orderlies and a doctor present, we were told to go to our beds and await examination by the doctor.

Ten minutes later a doctor came to my bed and asked what the problem was. I told him I had toothache, his retort was, What a soldier! Stung by his remark I rose from the bed and said, I didnt ask to come here, and made for the door. He laughed, told me to go back to my bed and said he would attend to me later. Not too long after a medical orderly told me the doctor wanted to see me in the courtyard. I went to the courtyard where the doctor was standing next to a sandstone chair, he told me to sit. Im not letting you touch it I slurred. He smiled and told me he wouldnt touch it but just wanted to look in my mouth. I opened my mouth to comply, Hah, its bad he said. He had by now placed his both legs between mine, Open again; as I did he slipped a plate into my mouth and signalled with his eyes to the two medical orderlies who were standing behind the chair. They grabbed my arms and shoulders while the doctor prised my mouth open and inserted the forceps, my head was in a firm grip when he started to wrench at the tooth. I thought my head would explode. I could feel the pain from my toenails right up through my body. I was about to pass out when I felt the tooth loosen from the gum. I opened my eyes and there he stood with the tooth still in the forceps. It was bad, there are ulcers under the tooth, he told me.

He told me to rest, so I did. I was exhausted. For almost a week I had suffered excruciating pain and had undergone horrendous treatment. There had been no drugs to dull the agony and I had not eaten any solid food. I lay on the bunk for a while, and then decided I would leave for the Front.

I left the castle, not bothering to inform anyone of my departure and walked toward the Front line. I trudged on for miles and miles, until eventually I came upon a building at the foot of the hills which was being used as a cook house and Medical Station for the British Battalion. The body of the structure was being used as the cookhouse. There was a tunnel driven right through the hill behind which I walked down, it must have been around 30 yards long and there were enormous jars set into each side of it.

Back at the courtyard I come across Doctor Bradshaw and after a short rest asked him for directions to the Front line. He told me to carry on along the road I had come by, and to follow it up the hill. I did this and shortly into my journey I encountered five young Spaniards who had lost their Battalion. I beckoned them to follow me and as we proceeded up the road, we were soon joined by more young natives.

It was now dusk, we could tell we were nearing the Front as we could hear sporadic firing. I organised the young men so they were walking in single file, as we turned a corner we could see a group of men gathered at the side of the road, as we neared them I became aware that there lying on the road was Tom Wintringham with a bullet in his leg. Thank God youve come, he said looking at me. What he meant and why he had said that I dont know. The only explanation I could think of was that he associated me with Cunningham who had shown his capabilities at Lopera. He was carried away by stretcher and we cautiously proceeded up to the front. I asked a member of the Battalion what the position was there. A bloody shambles, he said. The machine gun company has been captured and no one seems to know what is happening.

My entourage of 18 young Spaniards and I left the road and began weaving our way carefully through the olive groves; suddenly we were confronted by a man who raced madly toward us screaming. Theyre coming, theyre coming. It was later discovered that he had panicked and set fire to our own ammunition dump. After this episode, we proceeded with even more caution. As we neared our destination I saw a man I recognised, striding purposely toward us, it was Jock Cunningham, I called out to him and he crossed the road to join us.

Eventually we reached the first of the remainder of the British Battalion; there was not one Company Commander left! There was only one man responsible for holding this small group together and that was Political Commissar, George Aitkin. Jock told me to take the young Spaniards right to the end flank of the line. Once there I spaced them five yards apart and warned them to be on the alert. We waited there in the pitch black dark of night.

The last weeks lack of sleep and poor health were catching up. Now and then I would feel my eyes droop as I nodded into a doze; I shook myself and remained vigilant and alert as I had instructed the young men to do.

At first light the air became filled with the horrifying, shocking screams of the enemy attacking, all hell broke loose and the young Spaniards, shrieking, Moors, panicked and ran for their lives. A tank appeared in the road, Cunningham swiftly ran toward it and placed a dinner plate in the middle of its path, and he tank halted, turned and went back the way it had come.

By now the position was impossible to defend and Cunningham ordered the men to retreat to the other side of the road into the olive trees. What was meant to be an orderly retreat became total chaos as panic set in and I saw men running for their lives into the groves. A machine gunner who had abandoned his gun, turned back to remove the pin from his weapon when he became overwhelmed by the enemy. I too began to run; a bullet struck my helmet and went spinning off in front of me. I hurtled down the hill and lay behind a large rock, looking around I saw the silhouette of an enemy on the skyline. I fired, and watched as he crumbled and collapsed.

The order then came, Make your own way back to the cookhouse. When we arrived there were around 88 men assembled there. Cunningham then issued the order to line up. There followed a scene I will never forget. A tall, white faced, ginger headed man held a flag in his hand. He held it high. Cunningham led as we marched defiantly back, loudly and proudly singing the International. Numbers of stragglers joined with the French and Spanish. When we passed, Commander Klaus and his staff applauded loudly and hailed us with salutations of Bravo.

We marched back. By this time darkness had fallen. The scene was nightmarish among the olive groves, with orange stabs of enemy bullets stuck in the trees; we ran from trunk to trunk seeking cover. A French Officer, who appeared to be drunk, wide eyed and screaming, was urging us forward, while he stood apart in the midst of the trees. As we continued forward, still diving from tree to tree, both I and an Irishman lunged for the same one. As we did so the Irishman gave a grunt and fell to the ground. I dragged him back 20 yards to where the Red Cross was stationed. The medics pronounced him dead from heart failure; he hadnt been hit at all.

I returned to find the attack seemingly abating, we held the position till morning, when a fresh attack broke our ranks again but we quickly reformed and regained our positions. During that early morning attack a few of our men were captured, among them Big Frank Ryan, leader of the Irish men in Spain.

We then took up positions and a Spanish Battalion was in front of us. We were to support the line if it broke. Cunningham began to reorganise the Battalion, Malcolm Dunbar was our Company Commander, and I led a small section which included Condon.

We were lying on the crest of the hill, ten yards behind us there was a small sheer cut in the embankment, about 10 yards long and 6 wide, an ideal spot to protect you from the shelling and bombing. The night was cold but when the sun came out it got hot very quickly. We lay in our positions when, Condon, who was lying five yards from me said, Lets go behind that rock face. Dont talk bloody daft, I replied. We must stay in our positions. He mumbled something; I couldnt quite make out what he had said, so we lay in the hot sun waiting.

About half an hour later, Condon, without warning, stood and ran toward the enemy. Sensing something was badly wrong I ran after him and tried to reason with him, to persuade him to come back. There was a total lack of comprehension, so in order to stop him going further into danger; I punched him on the chin. He spun around and raced the other way, his eyes were blazing and saliva dripped from his mouth on to his beard. I ran to where Dunbar, Company Commander was, and asked for permission to leave my position in order to see to Condon. He told me to take someone with me; I motioned to a young Welsh soldier to come with me. Condon had now slackened his mad, manic rush and was now just ambling along like an enormous crazed bear.

I caught up with him and managed to get him to the ground whereupon he began screaming and fighting furiously. I managed to grab one arm and pushed it to the earth, I shouted to Taffy to hold this arm while I attempted to wrestle the other arm down. But Taffy, scared out of his wits, let the arm go. With his free arm Condon had managed to pick up a large rock, I felt it whistle past my head as I rolled off him. Condon stood and started to race away again. Young Taffy picked up his rifle and said, Shall I shoot him? Dont be so bloody stupid, just follow me, I replied.

We went after him keeping at a distance, he was still mooching along, a great bare like creature, when he stepped into a clearing where a posse of young Spaniards were sitting around a fire cooking their dinner. Condon walked right into them and they scattered like chaff in the wind. He grabbed some of the discarded food and was munching away when he caught sight of me. He scrambled to his feet and climbed up an olive tree. I tried to reason with him but just couldnt get any response or reaction. We were now quite near to the cookhouse where the medic would be, I told young Taffy to go and tell him what was happening.

For twenty minutes I tried to reason with him, but he was past all rational thought and would not be reassured. Into the clearing came Dr Bradshaw along with three other attendants, he signalled to me to keep Condon talking while two of the men crept silently behind the tree, they had a rope which they slung over the tree and used to lasso Condon to the ground. We then pounced on him, and held him down while the Doctor injected him. He slowly went under and was lashed to a stretcher and carried in the direction of the cookhouse. With the doctor leading we lurched forward and progressed into the hillside tunnel, (for about 20 yards?) to the coolest part.

I walked out in to the courtyard, leaving Condon still strapped to the stretcher. I sat on a wooden bench and broke down. I was exhausted both mentally and physically and extremely worried about Condon, who came from the same town as me. The doctor told me to rest, that he would send a messenger to my Commander and explain the situation. As I sat there in the sun the cook emerged from the tunnel, he asked if I would help peel potatoes and I agreed. He was the same man that led us up the hill, carrying a flag, while we all sang the International. His nerves and gone and this is why he had been assigned to the cookhouse, as we sat there peeling the spuds I noticed how nervous he was, any machine like sound would have him ready to dart off.

He went off to get more potatoes and while he did this I went into the tunnel and groped my way to Condons stretcher, he was just coming round. I asked how he was feeling. He said he was shaky but feeling better. I undid the ropes holding him down and told him to rest, then made my way back to the cook. As we sat chipping away at the potatoes, sitting near the mouth of the tunnel, there came an almighty roar, it became louder and louder, nearer and nearer. The cook took off in terror; he dived into the tunnel but was back out in seconds. I stood in amazement; I had never seen anyone move so fast in my life. It reminded me old films, where the trick photography made people appear to flash from place to place in milliseconds.

I looked toward the tunnel and could see what had caused him to rebound so rapidly. There, emerging from the mouth of the channel into the daylight was Condon. Walking with his arms dangling apelike, eyes glazed, hair awry and with dried saliva matting his beard. He looked horrendous! The impact and subsequent disappearance of the cook was shot in the arm to Condor, who looked at me with a glint in his eye as we both doubled up with laughter. Once we had recovered from the hilarity we sat together on the bench, I suggested he clean himself up, but the wicked gleam in his eye told me he hadnt finished yet, was going to exploit the situation to its fullest.

Halfway down the tunnel a hold had been made which allowed the smoke from the cooking to filter slowly out rather than up which would have betrayed the position of the cookhouse. Condon whispered something to me then disappeared. Within five minutes there was one hell of a hullabaloo coming from the cookhouse. The cook ran out screaming and swearing, shortly followed by Condon who was having a ball. The cooks language was lurid and explicit; he had obviously been badly shaken on discovering Condon, in his present hideous state, shuffling up to him in the dark tunnel. Luckily, once he had recovered, he saw the funny side of it.

Later that evening Dr Bradshaw returned from a tour of the front line, he told me he was sending Condon to a rest camp for a short while, so early next morning I said goodbye to him and went back to join the Battalion.

On my return I found that the enemy had been held and the International Brigade along with remaining Spanish Battalion proceeded to dig in, so it now became stalemate, with both sides reverting to trench warfare. The enemies attempt to cut off the Valencia road to Madrid had been thwarted.

Cunningham was now in command of the British Battalion; our depleted ranks were made up with the influx of new British Volunteers. New Company Commanders were appointed; I was now in Battalion Headquarters as a runner for Cunningham.

The flurry of attacks had now subsided and except for intermittent sorties and sporadic attacks of shelling, the occasional air bombing from enemy aircraft, things had settled down somewhat and we were inspired/rejuvenated by Paul Robeson who sang to the Battalion on the Front line. Earnest Hemingway also came to interview and photograph Jock Cunningham who insisted I be included in the photograph.

I well remember one incident when Dave Springhall, who was correspondent for the Daily Worker, came to our headquarters. I was holding a German Luger pistol which he admired, and eventually persuaded me to give him. At that exact moment the enemy launched a sharp attack. Springhall jumped into the trench leading to the front, within seconds he was back, a bullet through his cheek! He was obviously out of shape, the short spurt had caused him to open his mouth wide, and otherwise the injury would have been more serious. I laughed and said, You wont need that pistol now. He glared at me and shook his head.

We travelled back to Albacete, where Jock Cunningham told me that the Brigade had decided to repatriate the No1 Company, the oldest serving Company of the British Battalion.

From the talk I had with Cunningham, I gathered he was under a cloud with the Party in Britain, but he wouldnt elaborate on this question. I felt, that if he was, under a cloud, he was being made a scapegoat, so because of this I decided to return to the No 1 Company. It had been suggested I should go to Officers Training Camp, and was thinking this over when I decided to go home because of the suspicions I had about the future of Jock Cunningham.

Cunningham had called me to the dugout and asked how I would like to go home. I thought it was a joke, until he explained they had selected five men to go home to tell the rest of the workers of Britain what was happening in Spain, in the hope of getting more assistance for the Spanish Government. He said it was imperative for the morale of the Battalion that we return to Spain within a month.

We travelled from Albacete to Barcelona; in our group was Churchills nephew, Giles Romilly. In Barcelona we waited for clearance from the British Consulate to apply for emergency passports to return home. One of my most treasured souvenirs of the war was a crescent shaped knife, beautifully decorated, my only keepsake, my pride and joy. Giles Romilly had seen this and offered to buy it from me. I refused all offers. I kept it safe and snug in my knapsack. During the night a friend and I went for a drink and when we returned to the barracks we were told that Giles Romilly had gone home. I quickly checked my knapsack, only to find my treasured souvenir had vanished.

We had to wait a further two days before we were able to travel. At the interview, with a secretary of the Consulate, we were asked if we had been fighting for the Spanish Government. We all replied that we hadnt, and had come to Spain to work and had no political affiliation. He wasnt convinced, and when Reid, one of our party asked could he take home a bullfighting suit, then called him comrade, I knew we hadnt conned him!

However we received our emergency passports, and boarded the train which would take us to Perpignan, from there we went to Toulouse. When we arrived and stepped on to the platform, we were met by the French police who promptly put us under arrest. We were interviewed by a young woman who spoke English and who put the same question to us. Had we been fighting for the Spanish Government? We insisted we had gone to Spain to work. She was able to tell us exactly where we had been and what Battalion we were in. Doggedly, we refused to admit our involvement with the International Brigade. We were at the police station for two hours until eventually a lawyer came and secured our release. Once again we were on our way. We arrived in Paris and were met by some French comrades who took us around the offices of LHumanite where we met Jacques Duclos the editor, who had been elected as a member of the French Communist Party Central Committee in 1926.

When we landed at Newhaven we were picked out, one by one, from the long line of passengers, and then taken to a little room where we were searched and questioned. We were then put aboard a train and locked in a carriage until we reached Kings Cross station, when were then allowed to go our own way. We decided to report back to King Street Communist Headquarters where we met Harry Pollitt, Secretary of the Communist Party of Great Britain. Harry Pollitt was greatly influenced by his mother's socialism, much as I had been. He was not very enthusiastic, and said he opposed the idea of sending us home because it might have an adverse effect on the morale of the Battalion if we did not return to Spain. However, he gave us advice on how to speak at meetings and suggested we go to the News Chronicle offices to tell our story to the editor. During our discussion Pollitt stressed the importance of our returning to Spain and asked us to report back in one month.

We proceeded to the News Chronicle offices where we met the editor A.J.Cummings, after a brief discussion he handed us over to a reporter named Geoffrey Cox, who in 1936 when the Spanish Civil War broke out, was sent to cover the heroic resistance of Madrid. His experiences there provided a short book, Defence of Madrid (1937). He asked us many questions then promised we would receive a copy of his book.

We left the News Chronicle offices, and after saying our goodbyes, all went our separate ways. For me it was back to South Wales. Before I left London, I sent a telegram to the local secretary of the Party asking him to inform my mother, who was a widow that I would be home the next morning. I also asked him to convene a meeting of the local party.

When I finally returned home, the battle wary warrior, I was taken to task by my mother because I hadnt sent the telegram directly to her! I explained that I was concerned that a telegram would distress her, so, for her benefit I had sent it indirectly.

The Secretary of the local Communist party complained that I didnt have the power to order a meeting of the local party. I apologised and agreed, but tried to explain that I felt the matter of support for the Spanish people might just take some precedence over other matters.

Later that week I was informed that the editor of our local paper, who had previously printed one of the letters I had sent to my mother from Spain, would like to see me. This local paper was owned by a Liberal and was one of the few papers that had supported the Spanish Government.

When I eventually met him, I fancied I saw a look of disappointment on his face. Instead of a dashing figure, reminiscent of the swashbuckling, heroic images presented by Errol Flynn, he saw a short stocky man who did not remotely resemble the notion of the romantic, idealistic Spanish combatant volunteer! However, he did give us what we needed, publicity and support for the Popular Front Government of Spain.

The following weeks were spent speaking at meetings. I was not a good speaker, but did my best to bring home to people the terrible tragedy that was happening in Spain. Often, when the meetings ended, men would stay behind and ask how they could get to Spain and join the International Brigade. The only information I could give, was to tell them to get in touch with the local party leader.

Soon it was time to report back to London, and then back to Spain.

Throughout my time on leave I was asked many times if I intended going back to Spain. Once by the editor of the local paper, and always had to reply in the negative. This was very necessary because by now the policy of Non-Intervention, sponsored by the British and French Government was now fully operational, and volunteers were experiencing great difficulty in getting to Spain.

One morning, very soon, too soon, and after a tearful goodbye to my family, I caught a bus and quietly left Aberdare. Once again I was on my way to Spain.

I arrived in London and visited some friends, one of whom told me he had volunteered for Spain, but was turned back at Newhaven by the police. We had a drink together - it was Coronation Night - King George was crowned that day. The next morning I started on my journey, the same procedure, a weekend ticket to Paris. I was warned to be doubly cautious this time.

Once I arrived in Paris I was to go a particular cafι, order a coffee, and ask for Rita. The trip across was uneventful, except for one amusing experience on the ferry. I went to the bar for a drink and noticed a group of North Country boys, all carrying small cases. I ordered my drink, then turned to one of the young men and asked, Are you going to Ritas?. He blushed, shook his head, and then left the bar.